Requiem for a Friend

The criminal investigation into Matthew Perry's death shows (again) the profound corruption of American medicine - particularly the part of it that prescribes and promotes addictive drugs.

There’s no addict like a medically enabled addict.

And no dealer is more dangerous than one wearing a white coat.

Last week, federal prosecutors in California charged five people, including two physicians, in the 2023 ketamine overdose death of actor Matthew Perry.

When he died, Perry was hopelessly addicted to ketamine, a dangerous short-acting anesthetic now sold to treat depression - on the thinnest evidence. But Perry was not acting alone. His enablers viewed him as a human pincushion with a wallet.

“I wonder how much this moron will pay” for ketamine, one doctor texted a second, according to the federal indictment. A few days later, in a scene straight from an anti-drug school special, the first doctor allegedly shot Perry up in a parked car. A Friend in need is a friend indeed… especially if he has thousands of dollars in cash to hand over.

The depth of Perry’s degradation was exceptional, evidence of the risks of fame and fortune. But, at a time when entrepreneurial doctors and recreational drug legalizers are working hand-in-syringe to erase the line between medicine and getting high, it was far from unique.

—

(You know what is unique? Unreported Truths! And it’s way cheaper than ketamine. Take the plunge.)

—

Three people have already pled guilty for their roles in Perry’s death. Two more have been indicted. The details of Perry’s final weeks can be found in the indictment and plea agreements prosecutors unsealed Thursday in Los Angeles.

I wrote about the tragedy of Perry’s halting efforts at sobriety last December, after his autopsy results were released. The indictment paints a grimmer picture, making clear Perry’s overdose can barely be called an accident. He was using extraordinary amounts of ketamine, as the people providing it to him knew. By the end, he was demanding and receiving six or more injections a day. Even the drug’s strongest backers do not recommend more than a couple of doses a week.

The biggest surprise is that he did not die sooner.

But arguably the most telling detail of all has received the least attention - and shows just how thin the line between doctor and pusher really is for drugs that get their users high, even when physicians are not breaking the law.

Perry, who found fame and fortune playing Chandler Bing on the hit television sitcom Friends, was an easy target for medical parasites. He had struggled with opioid addiction for most of his life.

In his 2022 memoir, he explained that his opioid abuse had left him in 2018 with “an exploded colon, a brief stint on life support, two weeks in a coma, nine months with a colostomy bag, [and] more than a dozen stomach surgeries.”

Even so, he needed three more years to quit opioids, finally doing so in 2021, according to his memoir. By then Perry had found ketamine.

By all accounts, ketamine’s euphoria is different and stranger than an opioid high and often includes a profound dissociation. But it is a high no less.

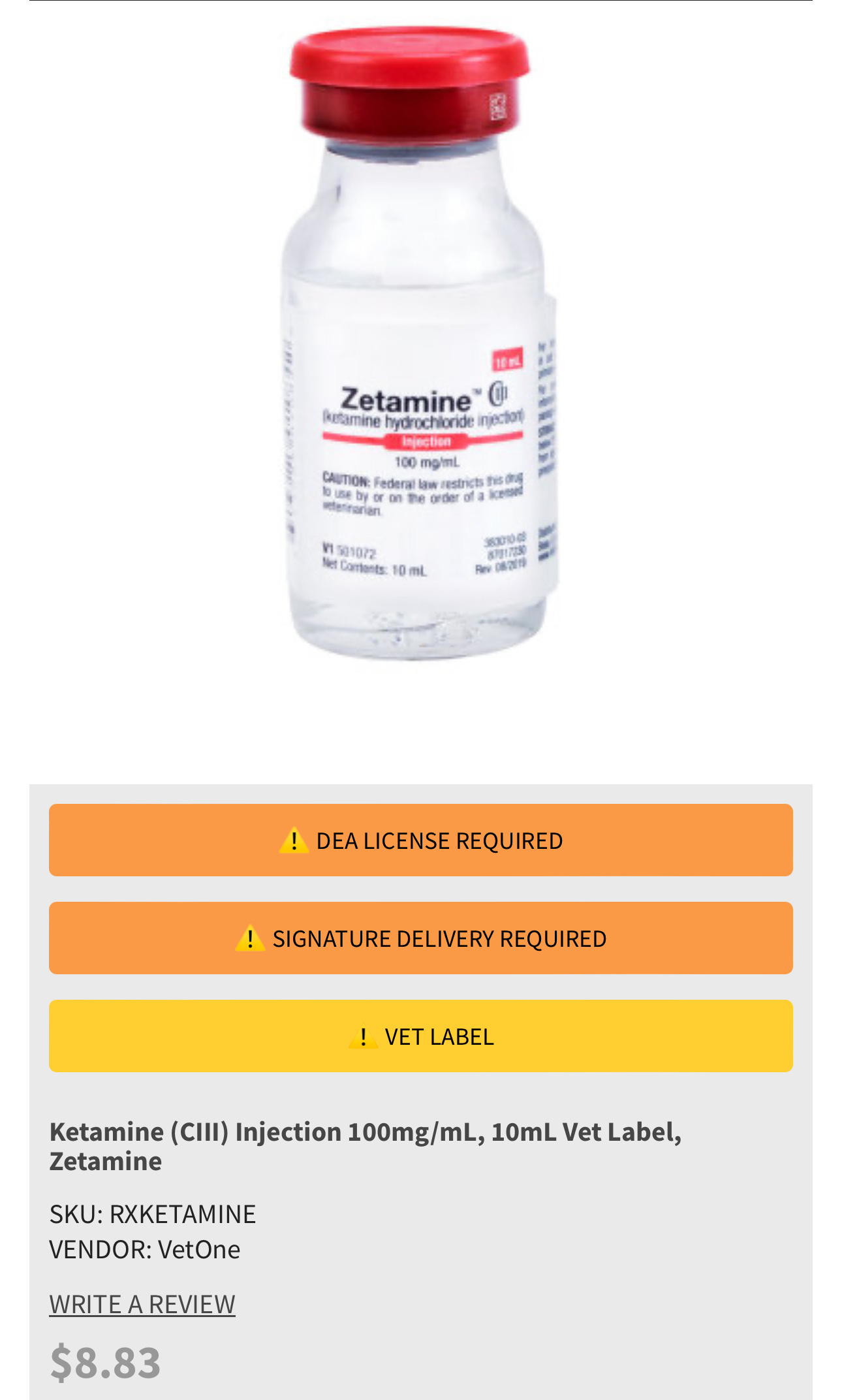

In his memoir, Perry wrote that using the drug was “like being hit in the head with a giant happy shovel.” Club kids call ketamine “Special K.” It’s also known as “horse tranquilizer,” because - yes - veterinarians use it as an anesthetic for animal surgeries.

—

(I give it five whinnies!)

—

Still, physicians now market ketamine for depression, part of a broader effort to rebrand drugs with high potential for addiction and abuse as medically necessary.

Amphetamines (Adderall, Vyvanse), benzodiazepines (Valium, Xanax), opioids (Vicodin, Oxycontin, fentanyl, which, yes, all be can useful for severe pain), and cannabis have all become essential to the American pharmacopeia. Billions of dollars are being spent to do the same for psychedelics. (Only cocaine remains stuck on the outside, which ironic since coke is actually a effective topical anesthetic.)

These drug classes work on different brain receptors and mimic different neurotransmitters - cannabinoid, dopamine, mu-opioid, NMDA, GABA, to name just a few. They have different mechanisms of action - agonist, partial agonist, antagonist - and different routes of administration: oral, intramuscular, nasal, sublingual, intravenous.

They produce different subjective (and objective) effects. The amphetamines are uppers. No drug has ever earned its nickname better than speed. The benzos are downers.

But for all their differences, for all the efforts to medicalize them, these drugs all have one thing in common: the core condition they treat is called not being high.1 And they are all very good at fixing it, at least for a few minutes or hours. (Not coincidentally, they are all also addictive to a lesser or greater degree, a tendency that can be objectively measured in clinical trials.)

—

(Wait, you’re not a horse! ALT: The pastel waves mean it’s working!)

—

Perry’s ketamine addiction seems to have spiraled out of control in September 2023. He was dead less than two months later. Ketamine’s high is potent, but it wears off quickly. By late October Perry was demanding shots every couple of hours, six or more intramuscular injections a day.

—

(Another hit. You know you want it.)

—

Two weeks before, on Oct. 12, he had already suffered a serious blood pressure spike and lost the ability to speak after receiving “a large dose of ketamine” injected by Dr. Salvador Plasencia, one of the two physicians charged in the case. Even that scare did not keep Plasencia and Dr. Mark Chavez from continuing to supply Perry with ketamine, according to the indictment and plea agreements.

Yet Plasencia and Chavez were not the only physicians giving Perry ketamine that day. In its most stunning and telling detail, the indictment notes Perry had earlier “received a ketamine infusion treatment from a medical doctor (“Individual 2”), at Individual 2’s office.”

The doctor is not further identified and was not charged with wrongdoing, presumably because he did not supply Perry ketamine illicitly and instead dosed him in his office, where he could be medically monitored.

Still. Did this unnamed physician not notice that his famous patient - who had not long before published a memoir about his desperate addiction to drugs of all kinds - was developing a bit of a jones for Special K? Did the needle marks not enlighten him? Did he not notice? Or did he - like Drs. Plasencia and Chavez - simply prefer to keep a good thing going?

—

(Original story here. One shot is a tragedy. Six shots a day is a crime.)

—

Earlier this month, the Food and Drug Administration finally put a line in the sand against the legalization of recreational drugs.

The FDA rejected the ridiculous effort to gain approval for MDMA - the club drug known as Molly or ecstasy, which combines amphetamine and psychedelic properties - as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, yet another squishy non-disease that almost anyone can claim to have.

As the poet of our time, Eminem, wrote about MDMA in “Drug Ballad,” his seminal treatise on recreational drug use:

Shit, six hits won’t even get me high no more/So bye for now, I’m gonna try and find some more

The usual drug legalization advocates made the usual complaints about the FDA’s rejection. But perhaps it - along with the grim details of Perry’s death - mark the beginning of the end of this generation’s effort to pretend that addictive brain intoxicants can serve as long-term solutions to psychiatric problems.

In the meantime, we’d all be wise to beware pushers with prescription pads.

For this reason I do not include antidepressants - either the SSRIs or the tricyclics - or antipsychotics - either first or second-generation - in this category. These drugs are easily distinguishable. They do not produce euphoria, they are not addictive (though antidepressants should be tapered), and with the minor exception of Seroquel they have no street value. No one walks into a doctor’s office demanding an antipsychotic; people beg not to take them and sometimes must be given them by force.

As a physician and surgeon I will tell you this. Two groups of people get the worst healthcare in America. The very poor and the very Rich. The poor because they lack access, the rich because they can get whatever they want.

Hard to stomach- but very glad you wrote this. Thank you for your stance on pot, speed, opiates and other drugs in general. I know this brings you criticism and hate, but the info needs to be published.