On what the Iraq invasion and mRNA shots have in common

And why it is so hard for the people in charge to understand when they've made a catastrophic mistake, much less change course

(NOTE: Dropping the paywall on this early because it has generated so much interest and discussion)

I’ve been thinking lately about the profound American failure I saw in Iraq in 2003 - and how it ties to the profound failure we’re all seeing right now.

I went to Iraq for The New York Times in September 2003, landing in Amman, Jordan, and then riding in a Suburban overnight through the desert to Baghdad. In my bags I had a bulletproof vest and $30,000 in cash for the paper’s bureau chief, John Burns. I will never forget how brightly the stars shone over the empty desert when we pulled off the highway a few minutes after crossing the border.

I hadn’t been a foreign correspondent before. But some experienced Times reporters had gone home after covering the invasion (though other great ones, including Burns and the legendary Dexter Filkins, remained). The paper needed reinforcements.

I was nervous. In late August, the United Nations headquarters in Baghdad had been bombed, killing 22 people, including its top diplomat in Iraq. Still, people who’d covered war zones told me not to overreact. These places are never as dangerous as they look from the outside. Baghdad was slightly bigger than Chicago and had twice as many people - almost 6 million in 2003. The risk of terrorism and violence was real, but manageable, they said.

For a while, it seemed they were right.

(THE STORY BELOW IS PAYWALLED AND SUBSCRIBER-ONLY FOR A WEEK.)

Times reporters shared a house on the east bank of the Tigris River, in downtown Baghdad. Across the water was the Green Zone - the fortified, walled district where L. Paul Bremer and the other Americans overseeing the occupation for the unfortunately named Coalition Provisional Authority lived.

(Dec. 14, 2004. Paul Bremer receives a Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award the United States offers. George Tenet, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, got one too. Can’t make it up.)

—

As a junior reporter, I didn’t get to Green Zone much. Bremer and the top generals and Iraqi politicians might make time for Burns or Filkins, but they weren’t interested in me.

So I looked for stories on the streets. In fall 2003, American reporters could travel around Baghdad and the rest of Iraq in soft - unarmored - cars with a driver and translator. Sometimes the translators carried pistols, though they weren’t really supposed to. That was it for security.

Similarly, the Times house was guarded, but not fortified. I suppose we still had some residual expectation that we’d be treated as non-combatants, despite the kidnapping and killing of Daniel Pearl in Pakistan the year before.

I even went to Falluja several times. But by later in the fall, Falluja - which lies in the desert about 40 miles west of central Baghdad - was becoming a no-go zone, barely safe even for toe-tap visits. Inside Baghdad, the car bombs were becoming more and more frequent.

In late October, the insurgents announced themselves by setting off six large bombs near-simultaneously all over the city. They targeted police stations and the Red Cross, proof that they were not going to respect the lines between combatant and civilian.

The day before, they had rocketed the al-Rashid Hotel in the Green Zone at a time when Paul Wolfowitz, one of the war’s architects, was visiting from Washington. Wolfowitz was unharmed, but the rockets killed an American lieutenant colonel.

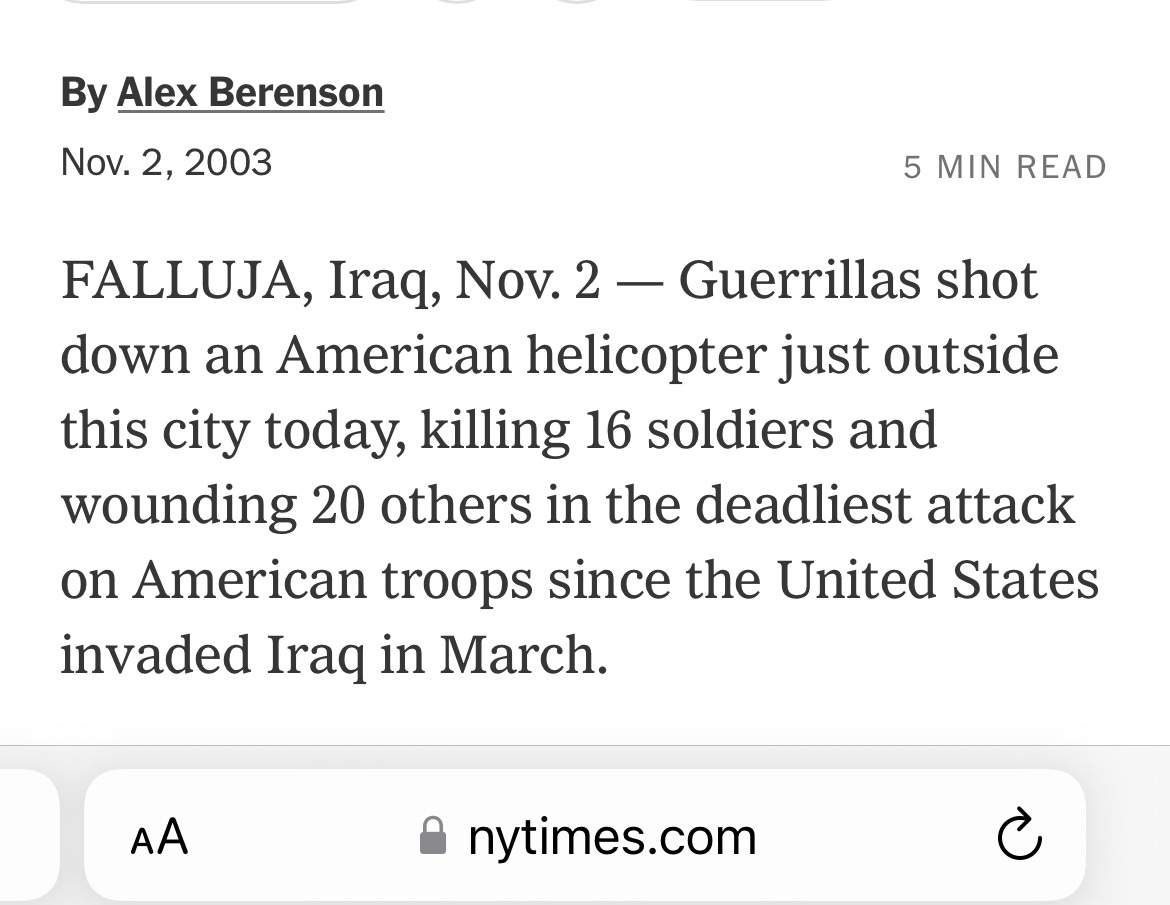

The next week, they shot down a Chinook helicopter outside Falluja.

—

The increasingly aggressive insurgency ran contrary to what the United States had believed - and promised publicly - would happen.

On May 1, President George W. Bush had declared “Mission Accomplished,” essentially calling the war over. That overconfident statement turned out to be one of the most disastrous mistakes in modern American history. (CORRECTION: Bush did not actually use those words. FULL NOTE APPENDED BELOW.)

I was hardly an expert on Iraq. I didn’t speak Arabic. I didn’t have access to the politicians or the generals. But I had one edge. I was out on the streets practically every day, and I could see for myself that a fuse had been lit.

It wasn’t just the bombs, the political violence, and the increasingly overt efforts by the Shia majority to take over Sunni homes in mixed neighborhoods. Street crime was out of control. The power kept failing. Most maddening of all, the “gas cylinders” - the propane canisters that Iraqis used to cook - were being rationed. A country with almost 10 percent of the world’s total oil reserves could not supply basic energy to its people.

Iraqis, even the Sunni minority that had benefitted from Saddam Hussein’s rule, had hated and feared Hussein. Yet since the Americans taken over, their lives had gotten worse, not better.

Yet the people in the Green Zone seemed to understand none of this. They and their neoconservative bosses in Washington were more worried about getting Iraq’s stock market started again and making sure American companies like Halliburton were the ones restoring Iraq’s oil fields.

(Yep, this actually happened:)

—

Really, why would they worry too much about what was happening outside the blast walls? The occasional rocket notwithstanding - and after the hit on the Rashid in October the United States dramatically stepped up its efforts to stop those attacks - life was pretty good inside the Green Zone.

The electricity and air conditioning worked. The dining halls - staffed by workers from poor, American-friendly countries like the Philippines - had plenty of food. There were gyms and satellite televisions and even a couple of hopping bars.

Meanwhile, leaving the Green Zone was a chore, and the worse Baghdad and Iraq got, the more of a chore leaving became. Civilians couldn’t just pop out, they needed a good reason and a security convoy, or even better a ride on a military helicopter.

So they rarely if ever left. When they did they mostly made short trips to the Baghdad homes of politicians like Ahmed Chalabi, who for a generation had made a fortune telling Americans what they wanted to hear.

—

Meanwhile, the violence targeting the United Nations and non-governmental organizations like the Red Cross had largely succeeded in forcing out those groups.

Whether the insurgents understood the effect driving out those organizations would have or simply attacked them because they were softer targets than the American military, their withdrawal worsened the myopia in the Green Zone. American administrators gained more power but became more isolated, without NGOs and UN to offer their own on-the ground perspectives.

So the only Americans who had any idea what was happening were reporters and the soldiers and officers who got “outside the wire.”

—

After all, the military was on the streets, patrolling and sometimes breaking bread with the locals. And many battalion-level officers - majors and lieutenant colonels - were very good and could see the situation was deteriorating.

But those officers weren’t really giving orders. They were taking them from the generals in the Green Zone, who didn’t get outside the wire much either - and who were locked in what was at best a delicate dance with Bremer and his civilian deputies at the Coalition Provisional Authority.

As the fall progressed, the mandarins behind the blast walls insisted that everything couldn’t be better. In fact, at one point, Brigadier General Martin Dempsey, whose Army division had responsibility for Baghdad’s security, told reporters the increase in attacks proved how well the occupation was going.

“Every move to return Baghdad to some level of normalcy was met by terrorist actions by those who don't want the coalition to succeed,” General Dempsey said.

This assessment would prove… optimistic.

—

Many factors drove the slide toward catastrophe, not all of which were under American control. Iran, which now faced American forces on both sides, had every possible reason to make the United States regret the invasion and worked tirelessly to foment violence.

But the biggest problem was the policy known as “De-Baathification,” which forced former members of Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party out of the the government and security services.

The United States was proud of the policy, which was the very first order the Coalition Provisional issued. It was meant as a parallel to the post-World War 2 “de-Nazification” of Germany, proof that the United States would turn post-Saddam Hussein Iraq into a modern democratic state.

But de-Baathification ignored several uncomfortable realities. Saddam Hussein had been in power far longer than Hitler, and without the Baathists the government could not function.

Further, Iraq was split along religious lines in a way that Germany had not been. Hussein and his top Baathists were all Sunni Muslim. The Sunnis, who included the tribes in Falluja and Ramadi, thus viewed de-Baathification as anti-Sunni policy.

Finally, when the Allies imposed de-Nazification on Germany, they had complete control, and the horrors of the war and Holocaust had turned Germany into a pariah nation. A proposal to turn Germany into an de-industrialized, agricultural state was seriously considered in 1945.

The situation in 2003 was very different. Iraq’s military had collapsed, but the United States had not established street-level dominance. The United States alone had 1.6 million soldiers in Germany at the end of World War 2 - ten times as many as invaded Iraq. Russia had millions more.

So all de-Baathification really did was anger Iraqi Sunnis, who became increasingly willing to partner with the vicious terrorists who flocked to Iraq from other Sunni Muslim countries for a holy war against the United States - and Iraqi Shias.

—

Of course, the Shia were not exactly innocents.

After a generation of being treated horrendously by Hussein, they wanted revenge - and their fair share of Iraq’s oil money. But de-Baathification badly worsened the tensions and meant the United States could never be viewed as a neutral broker between the two sides.

And in the decade-plus since the United States left Iraq, the Shia majority and Sunni minority have coexisted - not perfectly, but relatively peacefully. The sectarian conflict peaked during the occupation, not after.

Without the benefit of a time machine and a second universe, no one can know if the United States could have chosen a better strategy in 2003.

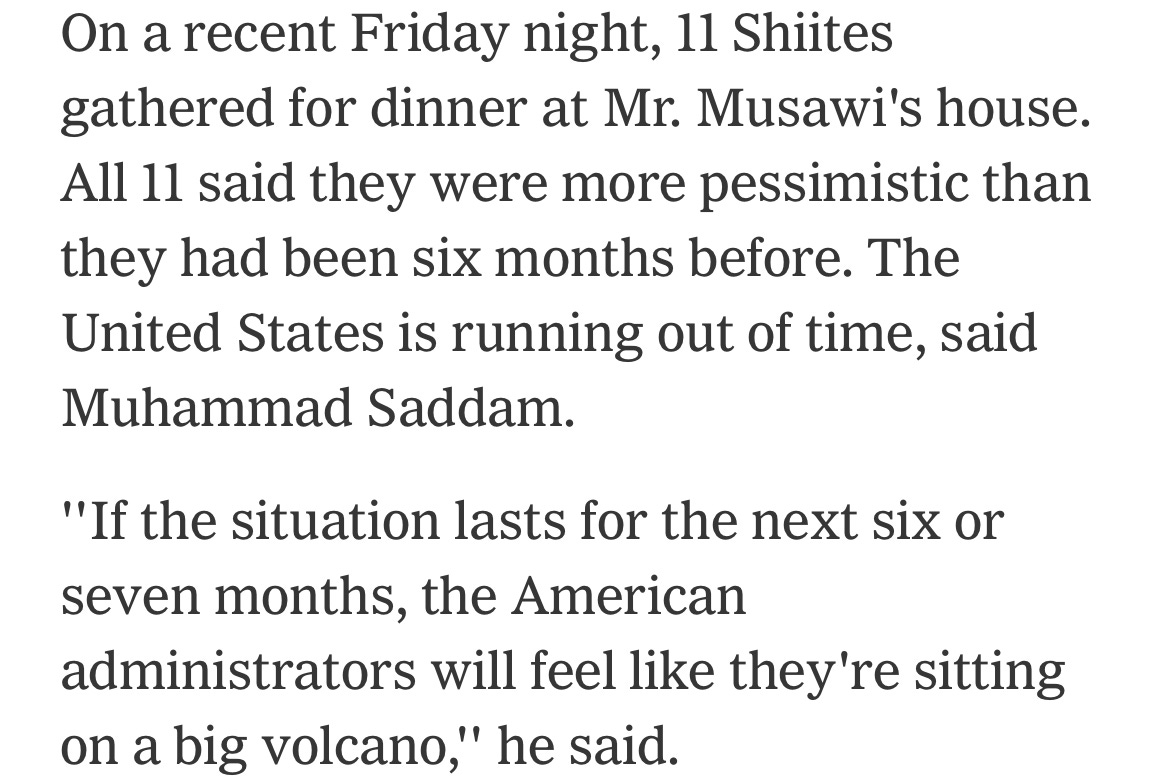

But what I do know for certain is that Bremer and the Bush Administration were willfully blind to the chaos on the streets. And that’s not hindsight. I wrote it at the time. The last story I filed for the paper during my 2003 stint was a long piece about the unraveling of security in a Baghdad district called Ghazalia, on the city’s western boundary. I wrote:

In ways large and small, life in this neighborhood of 150,000 people has worsened in the eight months since the United States toppled Saddam Hussein. Now the residents of Ghazalia, a suburban neighborhood that is in many ways a microcosm of the city, are nearly out of patience.

For the people who live here -- a mix of Sunni and Shiite Muslims, rich homeowners and poor renters -- the daily turmoil is exhausting and enervating. For the United States, it is a serious strategic problem, as was evident during dozens of visits to Ghazalia this fall.

The piece ended with a stark warning:

—

Muhammad Saddam was wrong, of course.

The volcano didn’t take “six or seven months” to explode. It took four. On March 31, Sunni insurgents in Falluja killed four American security contractors and strung them from a bridge. A few days later, Shia militia in southern Iraq revolted. For a few weeks it seemed like the American military might lose control of the whole country. Mission Accomplished!

The United States eventually reached a truce with the Shia (I was there for that too, but that’s another story), but containing the Sunni insurgency took years and thousands of American lives, as well as many more Iraqis.

—

This piece is already too long, so I am not going to belabor the obvious analogy.

For a few months the mRNA vaccines seemed to work as promised. Mission Accomplished!

The mRNA Covid vaccines provably began to fail barely six months after their rollout. Those of us outside the walls and looking at the data could see the reality.

But the people inside had too much invested in the jabs to recognize what was happening. Too much money, too much prestige, too much political power. And the further up the chain they were, the more divorced from the raw data they became, and the easier it was for them to hear only what they wanted to hear.

Besides, the vaccines were more than just vaccines. They were symbols of Western and specifically American technological superiority. They were a path forward.

The fact that they didn’t work was almost irrelevant.

Until it was.

There are two big differences, though.

First, we could and did send more soldiers to Iraq to fight the insurgents, but we cannot undo whatever the mRNA jabs have done to our immune systems with more jabs. The booster strategy has already failed, which is why countries all over the world are putting tight limits on future shots.

Second, Sars-Cov-2 is a far more implacable and enigmatic enemy than the Iraqi insurgents ever were.

Let’s hope it wants peace - in the form of low virulence - and not war.

As a veteran of these conflicts, Alex is correct. I hate to admit. I served as a civil affairs nco in Somalia, Afganistan, and Iraq. I supported these wars/Bush. We never made any of these places better for the long term. Our national interest was never threaten. I can remember being in Ramadi, 2004, with a FL ARNG infantry unit, and discussing the worsening situation, NOBODY above brigade level wanted to hear it. It is one reason why I now do not support the war in Ukraine. It is unlikely we will make things better in the long run.

Nice analogy to the Iraq war. But I think there's a better analogy: the economic collapse of 2008.

The so-called "vaccines" are TOO BIG TO FAIL.

TOO much money was spent/distributed/wasted.

TOO much political power was seized by the bureaucrats at all levels of government.

TOO much holier-than-thou was embraced by the compliant/gullible segment of society, which allowed them to control ALL society.