The people who brought you Covid are really hoping to make bird flu a thing.

Scare stories about a potential epidemic of H5N1 influenza have taken off this week, with New York Times asking if we’re ready for “Back-to-Back Pandemics.”

(Or maybe Back-to-Back-and-Belly-to-Belly pandemics?)

Worst of all, Neil Ferguson is now making H5N1 predictions. Ferguson is the British epidemiologist who helped stampede the world into lockdown in 2020 with dire predictions of Covid patients overrunning hospitals. The rules didn’t apply to him, though, he made sure his married (not to him) girlfriend could drop by even when he had Covid.

(Side piece exemption! In his defense, she’s cute:)

(SOURCE)

—

Anyway, this time around, Ferguson thinks lots of people could die from bird flu. Or maybe almost nobody. It just depends. But that’s no reason not to be scared!

Be afraid. Be very afraid.

—

(Don’t be afraid. Step up and subscribe.)

—

Or don’t.

In case you’re wondering, the H5N1 influenza strain is not new. Scientists first found it in Scotland in 1959. It probably existed long before that.

And yes, H5N1 is highly lethal… to birds, and to any humans who are unlucky enough to be infected with it. But it has never spread between humans - and the lack of human-to-human transmission is not a coincidence.

The genetic quirks that make H5N1 so effective at sickening birds mean that it is less than ideally adapted to infecting humans. As researchers wrote in 2019, the specific “preference” that helps make the H5N1 strain so lethal “can also impair replication and aerosolization.”

Again, this interplay between lethality and ability to spread for mRNA respiratory viruses is not new. Nor is it confined to H5N1. Or the flu. In the last 20 years, both MERS (Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome) and the original SARS have turned out to be highly lethal coronaviruses. But they barely spread, especially outside hospitals.

The biological realities of both virus and host are responsible for this seesaw.

At the molecular level viruses have to “choose” how to mutate the spikes that attach to human cell receptors, for example. Attacking cells deep in the lungs better may mean attacking those in the upper airways less strongly.

But even if a virus could somehow make itself incredibly lethal and highly transmissible, doing so might not be in its best interest. A respiratory virus that sickens hosts too efficiently reduces its own odds of surviving by quickly making that host too sick to move and thus carrying it to other potential targets.

Viruses like smallpox have a longer incubation period, so they can spread person-to-person before they make people very sick. Not coincidentally, they have a much higher infection fatality rate than the flu or Covid. The ultimate example of this is HIV, which people can spread for years before it sickens them, and which without treatment eventually kills almost everyone it infects.

But coronaviruses and influenza are NOT HIV. And they don’t want to be.

—

Simple thought experiment: Imagine a moderately dangerous, moderately transmissible coronavirus. It mutates in ways that makes it more dangerous. And more dangerous still.

Suddenly our middling little coronavirus is a supervirus, killing anyone unlucky enough to get it posthaste.

Danger Will Robinson!

Except. Even if superCovid hasn’t traded any theoretical transmissibility at the cellular level to increase its lethality, in reality its transmissibility is plunging because its hosts are getting so sick so fast. And with fewer new hosts, the supervirus has fewer chances to mutate to raise its transmissibility again.

It is caught in a trap of its own making.

I strongly suspect that in the absence of gain of function research - that is, human-directed engineering that simultaneously maximizes both lethality and transmissibility - influenza and coronaviruses may simply never be able to evolve in both ways at once.

Can I prove my comforting little theory? Like prove prove? I cannot. I’m not sure anyone can - not without spending a few lifetimes and a few billion dollars investigating viral transmission at the cellular level. Even then a lot of modeling and guesswork would be required. But it sure feels right, and it would explain the lack of any major respiratory virus pandemics between 1919 and 2020.

—

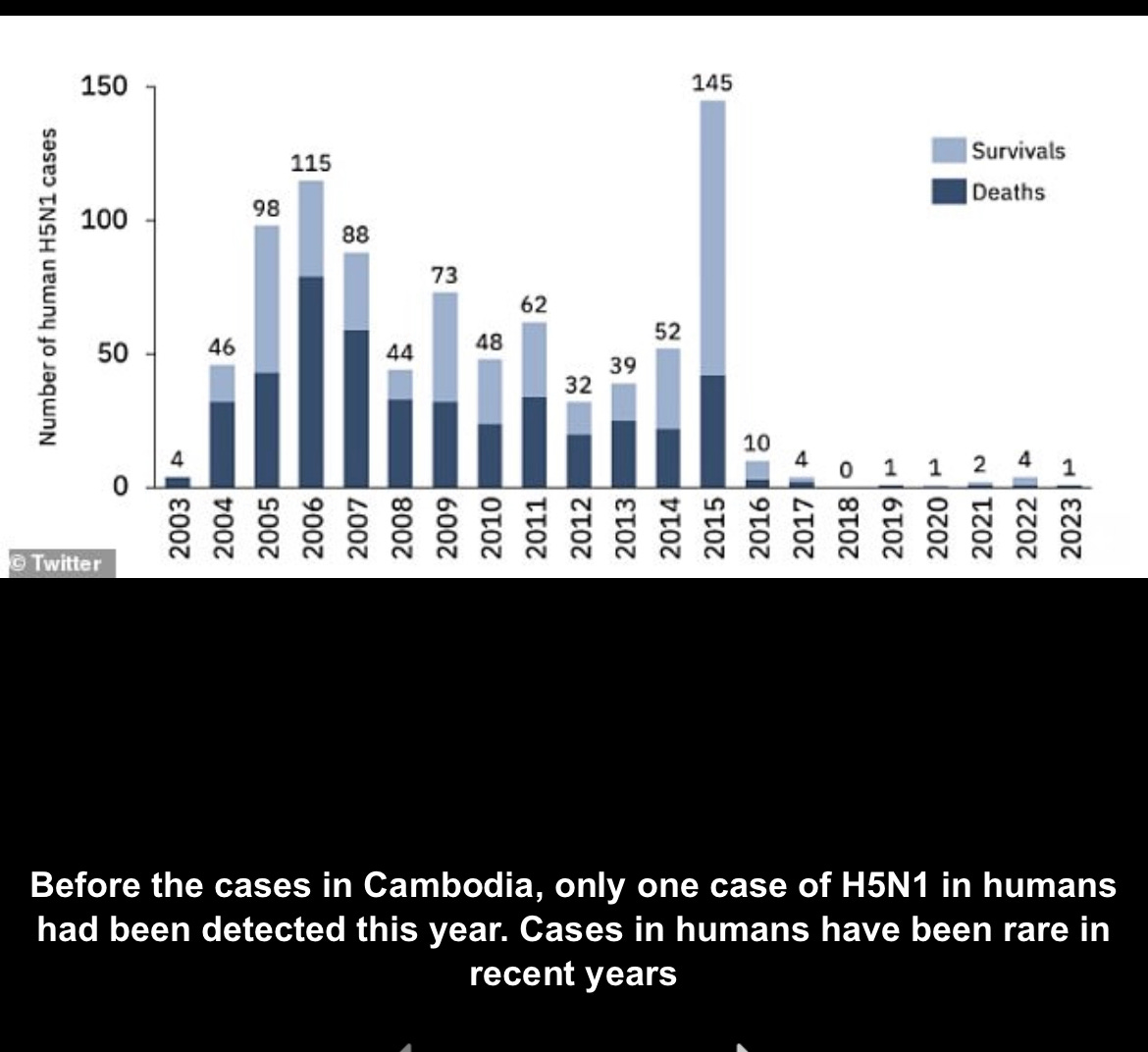

Maybe this time bird flu will break the rules. Maybe we have stuck so many chickens so close together for so long that H5N1 will hit the supervirus lottery and become both highly lethal and highly transmissible. But we’ve been breeding chickens on nastily crowded farms for a long time and this is what H5N1 human cases look like over the last 20 years:

(The bird flu outbreak will call you back later:)

—

So what’s really going on? Why the sudden interest in bird flu?

How do I put this politely?

The most likely explanation is more economic than biological. Covid supercharged spending on virology, epidemiology, and immunology. A LOT of people, and not just in the United States, made a lot of money on that gravy train.

But all good epidemics must come to an end - even in countries foolish enough to use mRNA vaccines (let’s hope, anyway) - and Covid is no exception.

What’s a good epidemiologist to do now?

Release the chickens!

We learned in med school that herpesvirus is one of the smartest ones. Lingers, finds a home in ganglia, but does not kill. Preserves the host, spreads easily. Sort of like politicians...

"Boy Who Cried Wolf" ends up killing us all because one day there will be a real deadly pathogen and no one will believe it....