The smug, Botoxed face of everything wrong with medicine in America (PART 1)

His name is Brent Saunders. He's a lawyer who made a fortune running drug companies while saying he didn't even want to try to discover drugs. Now he's lecturing Elon Musk on social responsibility.

(FIRST OF TWO PARTS: The Rise)

American medicine is sick.

The evidence is everywhere, from punishing insurance copays for crucial drugs to shortages of physicians for basic care to soaring maternal death rates.

The national numbers match our personal experiences. America spends twice as much per-person on healthcare as other rich countries, an extra $2 trillion a year - an unthinkably large number. Yet our lives are almost six years shorter on average than those other advanced nations. The gap has risen even as our spending has spiraled.

It’s almost as if the money has made matters worse.

But not for everyone.

—

(Meet Brent Saunders… and his (second) wife.)

—

Health-care executives have learned to profit from our broken system. They reap - in a phrase Tom Wolfe made famous in The Bonfire of the Vanities, his 1987 novel about the fall of a bond trader - its “golden crumbs.”

So much gold, so many crumbs.

Wolfe’s full line is even more telling, though:

Just imagine that a bond is a slice of cake, and you didn’t bake the cake, but every time you hand somebody a slice of the cake a tiny little bit comes off, like a little crumb, and you can keep that…

You didn’t bake the cake.

American physicians do very well. They earn far more than doctors in other rich countries and accumulate far more wealth (in other words, the higher salaries do not mostly go to repay medical school loans, despite what doctors sometimes say).

But the biggest earners in our system are generally not practicing physicians.

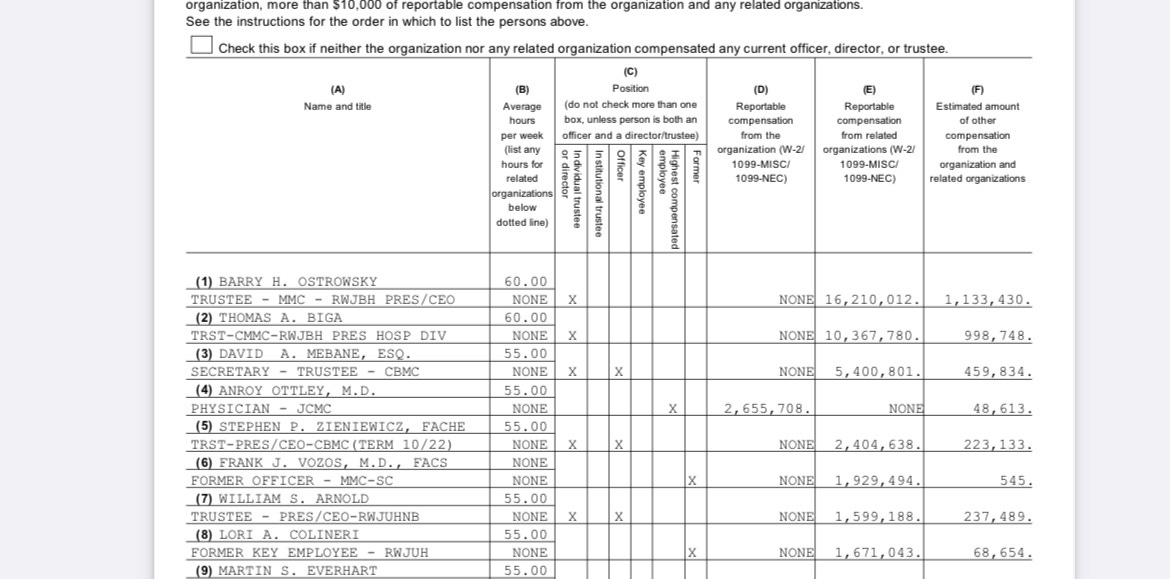

Most do not have MDs at all. Hospitals are huge businesses, whether for-profit or “nonprofit.” Their heads typically earn millions of dollars a year - like Barry Ostrowsky, a lawyer who made $17 million in 2021 as CEO of a nonprofit hospital system in New Jersey. (Glad to see the $178 billion in bonus federal Covid money that hospitals and other healthcare providers got was not wasted!)

—

(Nice work if you can get it: this IRS Form 990 shows what the top executives at RWJBarnabas Health, a New Jersey hospital chain, made in 2021.

ALT: He was working 60 hours a week! $17 mil isn’t even $6,000 an hour. A man’s gotta eat.

ALT ALT: How do you think they keep it a non-profit, folks?)

—

Yet even by those standards of medical avarice, of two-handed, open-mouthed, rules-are-for-thee-not-for-me greed and cynicism, Brenton L. Saunders stands out.

Saunders, a lawyer and MBA, now serves as chief executive of the eye-care company Bausch + Lomb. He took the job, along with a $6.5 million sign-on bonus, on Valentine’s Day.

Funnily enough, he had the same job at Bausch from 2010 to 2013, before beginning an odyssey across the pharmaceutical industry that made him over $100 million (give or take) over the next few years.

Along the way Saunders traded companies and jobs in a head-spinning series of swaps. He wound up just shy of the industry’s top tier, the globally known giants like Merck. In 2016, he nearly pulled off a deal that would have put him there, setting him up to run Pfizer. (Yes, that Pfizer, the one - full disclosure - whose chief executive I am suing for his efforts to censor me in 2021.)

—

(The medicine you need. For 20 cents a day. The truth has no side effects. )

—

Saunders’s rise was particularly impressive because even as he rose through Big Pharma’s ranks, he publicly scorned the idea drug companies might want to, well, discover drugs.

He focused instead on dodging taxes, firing employees, and searching out arcane legal loopholes to extend patents and keep the prices of drugs high. And for a while, it seemed nothing could stop him.

Saunders came to Wall Street’s attention for the turnaround he supposedly engineered during his first run at Bausch + Lomb. At the time, a private equity firm called Warburg Pincus owned the company, which had nearly collapsed in 2006 after Bausch’s contact lens solution was linked to fungal infections and blindness in users.

Under Saunders, Bausch’s sales grew almost 9 percent a year in 2011 and 2012, catching the attention of an aggressive publicly traded Canadian drug company called Valeant. In June 2013, Valeant bought Bausch for $8.7 billion. Warburg Pincus profited hugely, and Saunders gained a reputation as a young, can-do executive who could help modernize the slow-moving pharmaceutical industry.

Three months later, Forest Laboratories, which made the antidepressants Celexa and Lexapro, installed Saunders as its chief executive. Just five months after that, in February 2014, Saunders said he would merge Forest with an Irish drug company called Actavis. The move let the combined company avoid American taxes, even though it would still be run out of the United States.

—

At about the same time, Saunders made an even more cynical move - one that could have hurt patients if it had worked. Among Forest’s best-selling drugs was a Alzheimer’s drug called Namenda, which generated about $1.5 billion in sales in 2013.

But Forest’s patent on Namenda was set to expire in 2015, meaning that generic drug companies could introduce far cheaper versions that contained the same active chemical ingredient. So Saunders said Forest would introduce a new once-a-day “extended release” version of Namenda called Namenda XR — and stop selling the older version, which patients took twice a day, almost immediately.

The result was that Alzheimer’s patients would quickly have to switch to Forest’s new and more expensive once-a-day Namenda XR, even if they did not want to. No matter that these are vulnerable patients who can suffer from any disruption in their routine. Saunders said openly that forcing them onto the new drug would make it difficult for them to be switched back to the cheaper twice-a-day generic later.

“We believe that by potentially doing a forced switch, we will hold on to a large share of our base users,” Saunders said in a conference call in January 2014. (The New York state attorney general sued, and Saunders was eventually forced to drop the plan and keep selling the older version of Namenda.)

Meanwhile, Saunders had taken over the combined Forest/Actavis, now called Actavis. In November 2014, he used it to make his biggest deal yet, buying Allergan, the maker of Botox. The deal was among the most expensive healthcare acquisitions ever, valuing Allergan at $67 billion.

As with the Forest/Actavis merger, tax avoidance was a - if not the - big reason for the deal. The new Allergan could avoid American taxes, though it would actually be run out of Parsippany, New Jersey. Allergan-Actavis Deal Paves Way for Tax Savings, the Wall Street Journal explained.

—

By then Saunders had become a Wall Street golden child, and one of the highest-paid drug company executives. He made over $36 million in 2014. He was on track to become a “spokesman for the whole industry,” in the words of a later profile.

And he had even bigger - and more cynical - plans for the future.

(END OF PART 1)

Oh Alex, you've struck a nerve with me. I worked at Actavis in the legal department when the Forest Labs deal was consummated. I was also there while Brent and his buddies ran Actavis, and later Allergan, into the ground. You've got this man pegged to a tee.

His game is to move from company to company, loading himself and his cronies, who he always brings with him, with stock. He then seeks out a partner to buy the company at a premium so he and his buddies can cash out. He did it at Bausch, Forest and then Actavis/Allergan. He's looking to pull the same game at Bausch again, although he may have some trouble pulling it off this time.

All along the way, he does exactly what you say, cutting employees and funding for operations to make the company look good in the short term, boosting the stock price.

He is also a bald faced liar. I remember the whole Pfizer saga. He would get up on the podium during townhall meetings and swear up and down that he wasn't trying to have the company bought by Pfizer. And this was in answer to direct questions on the topic. We all knew what he was up to, because he also isn't very good at keeping secrets.

When Pfizer fell through he took to swearing up and down that he wasn't trying to sell the company's generics division, which he finally did as a prerequisite to the Abbvie transaction.

By the way, you forgot to mention his stunt of selling the company's patents on Restasis to an Indian Tribe to avoid a patent reexamination procedure using sovereign immunity. I know a little bit about that.

Overall, not a very nice person.

It's what has perhaps been a silver lining in this past plandemic in just how corrupt the Government-Pharma-Medical-Media cabal IS. Many here have probably known this is nothing new, and has been going on for decades and decades. Just astonishing how many AMERICANS still fall prey to the slick corrupt advertising where they are told to "ask their Doctor" The coddled, entitled and victim mindset of so many is appalling. Personal responsibility and independent critical thought for a life lived well is not rocket science, and yet Pharma continues to make HUGE $$$'s because they know how to manipulate the minds of sheep