RESENDING WITH PAYWALL DOWN: Could mRNA Covid shots help cancer patients?

A lot of you have asked me to comment on a Nature paper that came out last week and generated massive media hype. Here's my answer.

(NOTE: I sent a paywalled version of this yesterday - my first paywalled piece in several months. But I dropped the paywall earlier today on this article for free subscribers because of its importance to the debate around mRNAs. Unfortunately, Substack doesn’t seem to have sent free subscribers a second email with the whole piece. So I’m resending it to you — unchanged. You won’t be able to comment on this one, but you can see the comments on the piece yesterday on the UT homepage. Nonsense like this is why I don’t like paywalls. Anyway, enjoy.)

—

Since the mRNA Covid vaccines first began to fail in mid-2021, they’ve faced a long stream of bad news, from myocarditis to booster ineffectiveness.

But the black parade seemingly ended last week, when Nature published research suggesting some cancer patients who received the jabs outlived those who did not.

On cue, the Washington Post ran a breathless piece, and not-so-useful idiot David French chimed in about the “anti-vax movement” with a popular X post. I realized I’d better check out the paper. What I found was more interesting than I expected — though not necessarily good news for healthy people who have taken the mRNAs.

—

(NOTE: The paywall on this piece was supposed to last a week, but I am dropping it early because I continue to get questions on this study, which mRNA fanatics are promoting heavily, and I think the issue is too important to wait. I hope you will consider subscribing and supporting my work anyway!)

—

On the surface, the study’s results seem impressive.

The scientists examined about 1,100 cancer patients treated with immunotherapies, drugs that help a patient’s own immune system attack tumors.

Immunotherapy is the most promising cancer treatment in decades. Keytruda, an immunotherapy from Merck, now ranks as the world’s top-selling medicine. Still, many patients don’t benefit.

As most people now know, the mRNA Covid jabs make the body produce the Covid spike protein in its own cells, provoking a powerful immune system reaction.

And so a large group of researchers from M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, among the world’s top cancer hospitals, wondered if mRNA jabs might make immunotherapies work better.

They compared the life expectancies of 223 patients who had received Covid mRNA jabs within 100 days of starting immunotherapy with 871 who had not gotten the shots.

They found that those who had received the shots lived significantly longer on average than those who didn’t. People with lung cancer lived about 37 months on average if they received the shots, and 21 months if they didn’t. The results were similar for skin cancer, the other type of cancer they examined, though the number of patients was much smaller.

In the world of cancer treatment, that difference is huge. Even a couple of months of additional survival is enough to get a new cancer drug approved, usually for a six-figure price tag. In this case, the gap was over a year.

—

Those were the headline figures that led to last week’s hype.

But the results come with two huge caveats. One is specific to this study. The second is bigger a problem with every real-world “observational” study — and especially with real-world studies of vaccines.

The specific problem for this study is that the researchers looked at cancer patients treated with immunotherapies back to 2015 — the reason the non-vaccine group is so much larger than the jab group. Including more patients strengthened what researchers call the “statistical power” of the study, meaning that if it found a difference, that difference would be less likely to be due to chance.

But cancer care is a moving target, particularly with immunotherapies, which were relatively novel in 2015. Over time, even small tweaks such as the timing of doses may make a treatment more effective.

But the Covid shots were only given in 2021 and 2022, at the end of the period — when other treatments patients received might be more effective too. That timing gap might make the shots seem to help, even if they don’t.

Indeed, when the researchers restricted their findings to patients who had started immunotherapy treatment only during the pandemic era, and thus eliminated any treatment improvements that might have occurred from 2015 to 2019, they found a much smaller edge for patients who had received the shots.

The jabs were no longer associated with a statistically significant survival advantage over a two-year period in pandemic-era melanoma patients. They barely reached a statistical advantage in pandemic-era lung cancer patients.

—

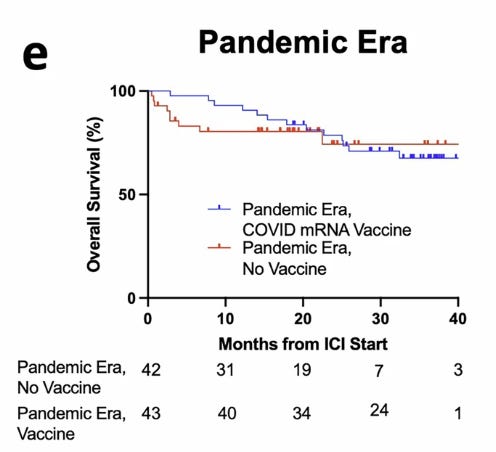

This graph compares outcomes in people with skin cancer who received mRNA Covid shots starting in early 2020 (the “pandemic era”), compared to those who didn’t get the shots.

See how the blue line — vaccinated people — has fallen a little lower than the red line by the end? That means fewer vaccinated people have survived - hardly evidence the mRNAs help as a cancer treatment.

—

The second difference is a problem in ALL “real-world” or observational studies, like this one.

In randomized controlled trials, patients are sorted by chance into different groups. Then they are given either treatments or placebos (pretend treatments like sugar pills or saline injections).

The point or the randomization is to make sure the treatment, and not some hidden difference between the groups, drives the difference in outcomes — that what researchers call the “independent variable” is truly independent.

But these patients weren’t in a clinical trial, so they weren’t sorted randomly. The patients who got the mRNAs might have been very different than those who didn’t. No matter how much researchers try to adjust after-the-fact for the differences between the groups, they can’t be sure they’ve succeeded.

In vaccine observational studies, this problem runs deep because of a problem called “healthy vaccinee bias.”

Put simply, doctors may withhold vaccines from people near the end of their lives, because they don’t see the point in causing even temporary discomfort. In this case, with patients being treated for cancer, it’s easy to imagine patients with the grimmest prognoses might have not have received the vaccines.

The chart above offers evidence of exactly that bias — the red line of unvaccinated skin cancer patients drops quickly at the beginning, but then it flattens out. The blue line of vaccinated is flatter at first, but then falls at the end. The two lines wind up in basically the same place (in fact, the blue line is slightly below the red line, indicating that vaccinated people were slightly more likely to die by the end).

Does that mean the mRNA shots helped at first and then lost their power? Or is it just that a handful of very sick unvaccinated people died quickly — but would have died quickly even if they’d been jabbed?

I suspect the answer is the latter. But there’s no way to know. That’s why scientists run randomized trials with patients enrolled prospectively — before the outcome is known.

—

If the observational findings are so messy, why do I think the study has any value?

Because the scientists also did a lot of “preclinical” work — that is, laboratory research — to try to see how mRNA jabs affect the immune system in cancer patients. They found intriguing evidence that the mRNAs might help immunotherapies work better, because the mRNAs stimulate the immune system to make huge amounts of certain proteins that help it fight tumors.

Neither the preclinical studies nor the observational results are nearly enough to get mRNAs approved as a cancer treatment. But they are promising enough to suggest that a real randomized study may be worth pursuing. (And that’s all they are.)

But what mRNA vaccine fanatics like French don’t seem to get is that this study has no bearing on the much bigger, more important question of whether the jabs help people without cancer.

If anything, it is a warning sign, because it shows how strongly mRNA jabs upregulate the immune system. That activation may not make sense for vaccines, particularly not for kids, who have very active immune systems already.

—

—

After all, chemotherapy works on cancer patients (sometimes). It kills cancer cells and shrinks tumors. But that doesn’t mean it’s good for healthy people.

In fact, as any oncologist will tell you, chemotherapy is basically poison.

No, I’m not saying the mRNAs are poison.

What I am saying is this study says nothing about their value as vaccines.