Lifting the kimono (uh-oh, trigger alert) a little more on Berenson v Twitter

How we got to a settlement

I don’t know what Judge William Alsup was trying to say yesterday with his order denying a 28-day extension of discovery deadlines in my lawsuit against Twitter. It’s unusual for a judge to reject a stipulation that both sides have agreed upon.

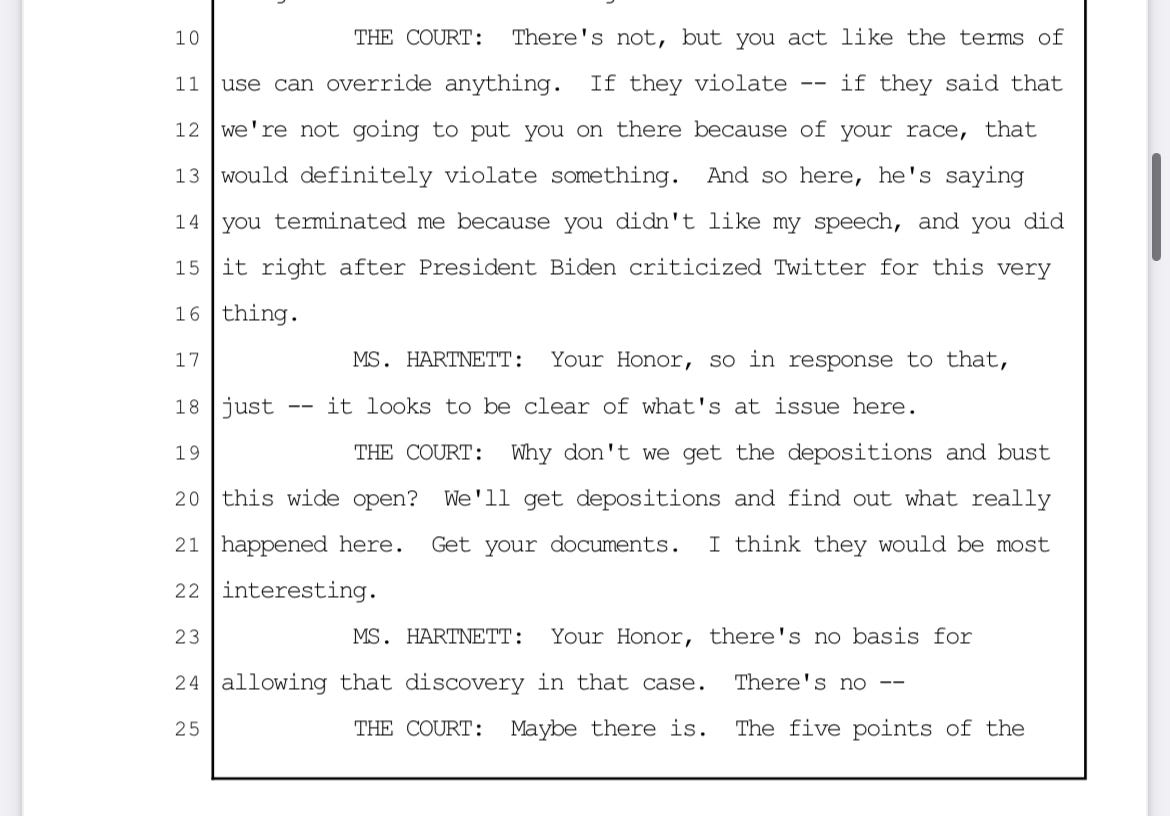

But one plausible theory is that in signaling his own desire to move the case into discovery as quickly as possible, Alsup was venting frustration that a settlement might stop that process. After all, in the April 28 hearing on the case, Alsup explicitly said, “We’ll get depositions and find out what really happened here.”

By the way, see where Alsup said that a Twitter ban on the basis of race “would definitely violate something”? Twitter’s explicit position is that it can ban users for their race, gender or anything else, if it chooses.

A lawyer for Twitter said so in June 2018 to California state court judge Harold Kahn in Taylor v. Twitter, another case in which a user alleged Twitter shouldn’t have barred him:

And, in fact, as to Your Honor's question about could a First Amendment speaker choose by gender, or age, or something like that, in fact -- I mean Twitter would never, ever, ever do that; it's totally contrary to everything it does… [But] does the First Amendment provide that protection? Absolutely it does.

—

Back to Berenson v. Twitter.

The first half of that April 28 hearing was stunning. Alsup repeatedly hammered Twitter’s lawyers. At one point, he told Kathleen Hartnett, the partner from Cooley leading Twitter’s defense, “Blather like that doesn’t help me at all.” Later he told off Kyle Wong, Cooley’s second lawyer, when Wong argued that a 19th-century law shouldn’t matter -

A law written 150 years ago, there's some pretty important laws from that era that we still enforce today, and just because you're a young guy does not mean you get to denigrate first principles.

These are very highly paid, well-trained attorneys - Hartnett clerked both for the Supreme Court and for Merrick Garland, the current attorney general - and Alsup left them tongue-tied.

By the time the hearing ended, I thought it was possible that Alsup would not merely allow the case to go forward on my breach-of-contract claim but at least one of my broader claims - either that California law defined Twitter as a common carrier and obliged it to carry all tweets or that Twitter was acting as a state actor on behalf of the federal government when it deplatformed me.

Had he done so, this case would never have settled. It probably would have gone to the Supreme Court.

—

But when Alsup made his ruling the next day, we found that he hadn’t been willing to go quite that far. He had tossed our broader arguments - with prejudice, meaning we couldn’t amend our complaint and refile them later - while allowing my specific breach-of-contract claims to proceed.

So Alsup had narrowed the case, turning it away from the broad legal implications we’d hoped it might have. The loss of the California constitutional and common carrier claims was particularly disappointing - courts have routinely rejected state actor claims, but our California claims were novel and well-pled and I really thought they deserved a hearing.

Still, Alsup’s ruling was overall a huge victory for us.

First of all, these ban lawsuits essentially never survive motions to dismiss. Federal and state courts generally interpret Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act as giving social media companies complete discretion over their decisions to toss users, as everyone from Donald Trump to Robert F. Kennedy has learned.

Second, Alsup had done something more than just letting the case go forward. He had taken it upon himself to order and schedule discovery and depositions. (Discovery is the process by which the plaintiff and defendant give each other information like emails that are relevant to the case; depositions are the questioning under oath of people who have that information.)

Further, in his discovery order, Alsup had set listed the information Twitter had to give us - and that list was extremely broad. In fact, it looked a lot like what we might have wanted if he had allowed our broader claims to proceed. Twitter had to provide all its communications about me with third parties - including government agencies.

—

With his order, Alsup made the information Twitter had to provide rather than my claim itself the most vital part of the case. (Was that an intentional decision on his part? I have no idea.)

Why? I thought we had a very good chance of surviving summary judgement - the next stage in the case - and a solid shot at trial too (though the jury would have been drawn from San Francisco, maybe the most Team Apocalypse city in the country). Yes, we could have won. And cost Twitter millions of dollars in legal fees along the way.

Won what, though? The specific facts in the breach of contract claim applied more or less only to me, because a Twitter executive had repeatedly emailed me to tell me that Twitter was aware of my tweets and had no problem with them. (You can bet Twitter will make sure its executives never say anything like that to a user again.)

But the breach of contract claim by its nature didn’t allow for a broader review of Section 230. In fact, it was not even clear that I could even force Twitter to let me back on the platform if I went to trial and won. Monetary damages might have been my only relief, and Twitter’s contract limits those to $100. Of course we would have fought that provision too, and maybe we would have won, but winning might only have raised the damages, not gotten my account reinstated.

No, what I really needed was the information Alsup was making Twitter give me. Those documents and emails and texts weren’t just unique reporting gold - they would tell me whether I had a future state action claim - not against Twitter, but against the government itself. What Twitter’s own employees were saying about me mattered much less to me than its conversations with outsiders. (I’m used to people saying bad things about me.)

We knew lots of fights were coming about discovery too, that Twitter was going to want a protective order so I couldn’t disclose what I learned and would claim attorney-client privilege to hide information even from me and my lawyers wherever possible. It’s no accident that Twitter’s trust-and-safety team - its censorship unit - reports to its general counsel. (She cries in public, but everything else is secret!)

But Alsup’s order was a powerful card, and I intended to play it. And his statements in April suggested he wanted to see the information too - and thus might be less-than-receptive to Twitter’s efforts for privacy.

That’s why on June 6, I wrote:

I will NOT agree to any settlement that does not preserve my discovery rights about third-party communications AND give me the right to publicize them. There are other things I will (and have) given up, you have to give to get, but this is the reddest of lines.

Note I didn’t just say I had to have discovery, I said I had to have discovery AND publication rights.

Now here we are.

—

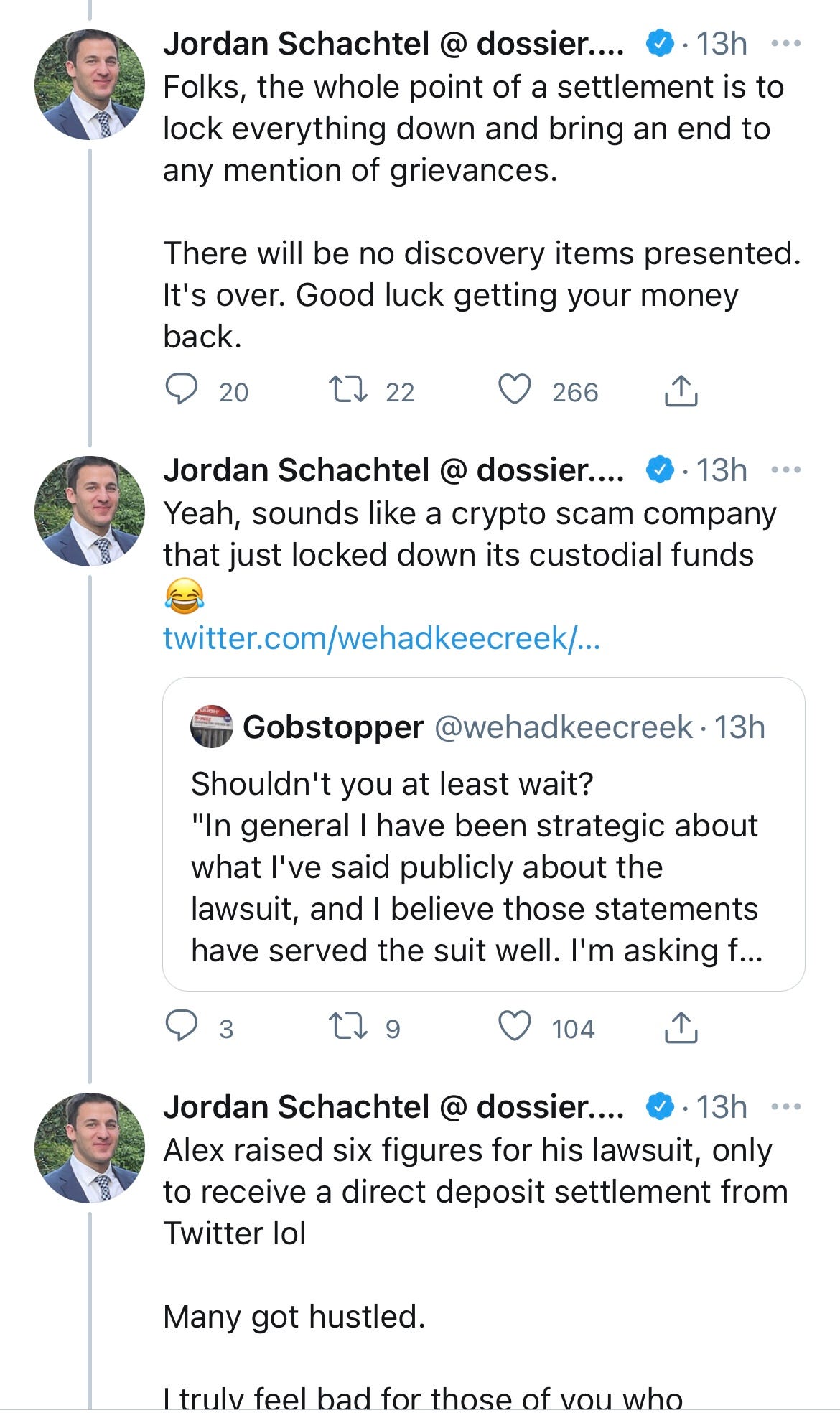

After I announced the deal with Twitter, bluechecks like Jordan Schachtel spent yesterday loudly and repeatedly claiming that I had solicited you for money under “false pretenses” and “hustled” and comparing me to a “crypto scam company”:

I am going to say this one more time. Jordan Schachtel does not know what we agreed to. Only Twitter and I know what we agreed to.

Yet I am still talking about this.

Jordan - who has 206,000 followers - may want to ask himself why.

And find a libel lawyer to ask what about the definition of “actual malice.”

Nope.

Too many words.

Not buying it.

If you can read between the lines here, Alex still has his eye on the prize: The truth about what is happening inside and outside of Twitter that is making a mockery of public debate and wielding gross censorship. I will be patient and see where this goes. My donation has already paid dividends to me.