Capitalism, except for the capitalists

What happened over the weekend is bigger than Silicon Valley Bank; once again the wealthiest, most politically connected companies and executives are proving the rules don't apply to them.

Back to the banks.

For a few hours on Sunday, they fooled me.

At 6:15 p.m. Sunday, the government and Federal Reserve announced they would guarantee all deposits at the two big banks they’d closed, Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank - removing the $250,000 limit on insured accounts to help prevent a bank run.

Taxpayers would not be on the hook for any losses, they said. The banking industry would pay for the extra insurance.

I didn’t think the deposit insurance should be extended at all.

When banks failed in 2008, we didn’t have unlimited deposit insurance, and we didn’t have widespread bank runs on healthy or unhealthy institutions. Very few individuals have more than $250,000 in their plain vanilla bank accounts (as opposed to brokerage accounts where they are saving for retirement).

So extending the limits at taxpayer expense to protect very wealthy depositors and - in the case of Silicon Valley Bank - venture-capital backed companies didn’t seem fair.

And we have limits on government backed deposit insurance for good reason. Without it, large depositors have every reason to chase the highest possible interest rates on their money, even at badly managed banks. Why? They know that even if the bank squanders their deposits on bad loans, they’ll get their money back.

—

(BAIL ME OUT! SUBSCRIBE NOW!)

—

This risk is not theoretical. In the 1980s, many savings and loans crashed after offering high-yielding deposits. As financial historian and journalist Roger Lowenstein explained yesterday in the New York Times:

When the Federal Reserve, under pressure of rising inflation, began to jack up rates, S.&L.’s had to pay higher rates to attract deposits…

Many switched to riskier assets to juice their returns, but as these investments soured, their problems worsened. Roughly a third, or about 1,000, S.&.L.’s failed.

—

But venture capitalists - led by David Sacks, a good friend of Elon Musk - spent the weekend screaming that bank runs would be inevitable if the government didn’t guarantee all depositors.

Many if not most of these folks had not-at-all hidden conflicts-of-interest - either personal deposits at Silicon Valley Bank or investments in companies that had deposits there. Nonetheless, they insisted that they were warning about bank runs solely because they wanted to save ‘Merica from bank runs!

Whether or not they were trying to worsen the crisis, their warnings certainly did. They essentially forced the government’s hand.

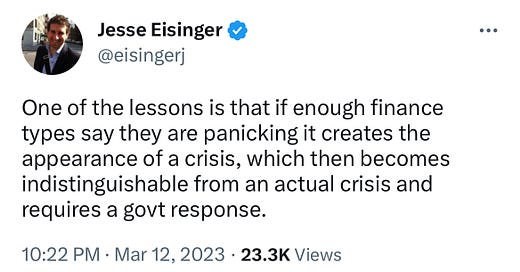

My old friend and colleague Jesse Eisinger (I guess he’s now a ex-friend, thanks to my reporting on Covid and the mRNAs, but that’s a story for another day) captured the dynamic nicely:

—

If regulators and the Treasury Department felt they had no choice but to guarantee all deposits, then forcing the industry to pay for the extra insurance seemed like the fairest option.

“Any losses to the Deposit Insurance Fund to support uninsured depositors will be recovered by a special assessment on banks, as required by law,” the Federal Reserve’s press release explained.

Yes, banks would probably wind up passing the cost along to customers anyway. But at least they’d upheld the principle that taxpayers shouldn’t - yet again - bail out the wealthiest Americans. “So the Fed found a semi-decent solution here,” I tweeted at the time, adding a warning: “The devil is in the details, of course.”

—

So it was.

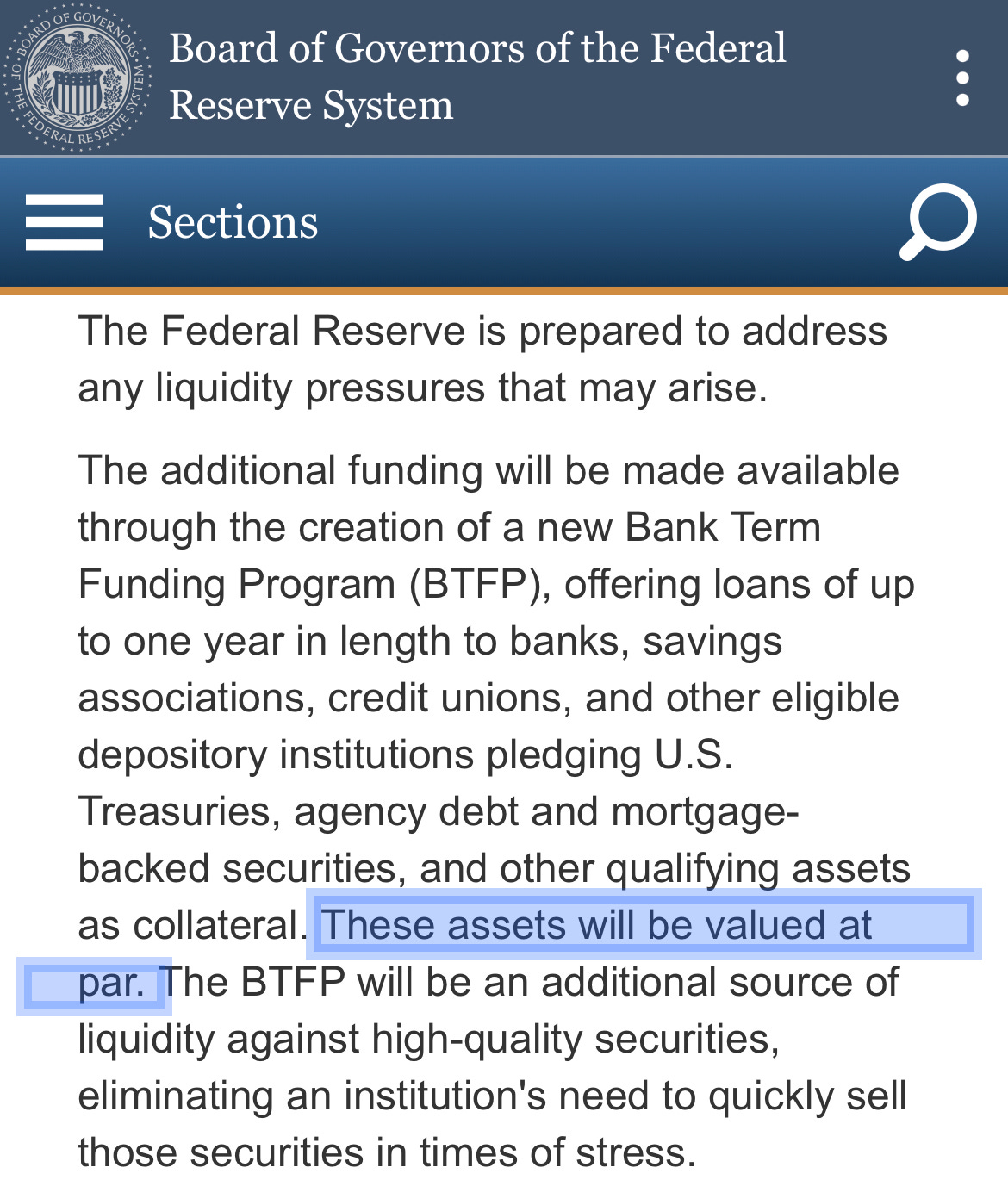

The deposit insurance extension got the attention, understandably. But the most important news on Sunday came buried in a different Federal Reserve press release, seven little words: These assets will be valued at par.

—

Why do those seven words matter so much?

The reason that depositors started pulling money from Silicon Valley Bank last Thursday wasn’t because they suddenly woke up and decided Silicon Valley had a weird-looking logo. It was because Silicon Valley had lost huge amounts of money buying low-yielding Treasury notes and mortgage-backed securities.

Bonds carry two kinds of risk, credit and interest rate risk. (Bearer bonds carry a third kind of risk, that they will be stolen, ala Die Hard. But bearer bonds don’t really exist anymore.)

Credit risk is obvious - if a company goes bankrupt and can’t pay back a bond, it’s worthless, give or take. Interest rate risk is more subtle. Bond prices rise as interest rates fall and fall as rates rise.

For a person who owns a bond and just plans to hold it until it matures, interest rate risk doesn’t matter much.

But for a bank, interest rate risk matters hugely.

A bank takes money from depositors and uses it to make loans or buy bonds (or other, more esoteric financial instruments). If the depositors want their money back, the bank has to give it to them. If it has to get that money by selling bonds when their value has dropped because interest rates have risen, it will lose money. A bond for which it paid $100 might only be worth $90.

But not to the Federal Reserve.

The Federal Reserve just told the world that it will pretend that a bond which is really only worth $90 is actually worth $100 - “par.” That’s what “these assets will be valued at par” means.

This program is similar to the way the Fed started to bail out banks in 2008, when it bought mortgage-backed securities that no one else would. That program, like this one, was supposed to be a temporary response to a crisis that threatened to destroy much of the banking system.

How’d that work out for us? Before the banking crisis of 2008, the Fed had under $1 trillion in assets. In bailing out banks that fall, it more than doubled the size of its balance sheet - to over $2 trillion.

Today the Federal Reserve has over $8 trillion in assets - loans and bonds that it has taken from banks (and since Covid, from companies directly). It is a larger and more crucial backstop to the banking system than it was 15 years ago.

—

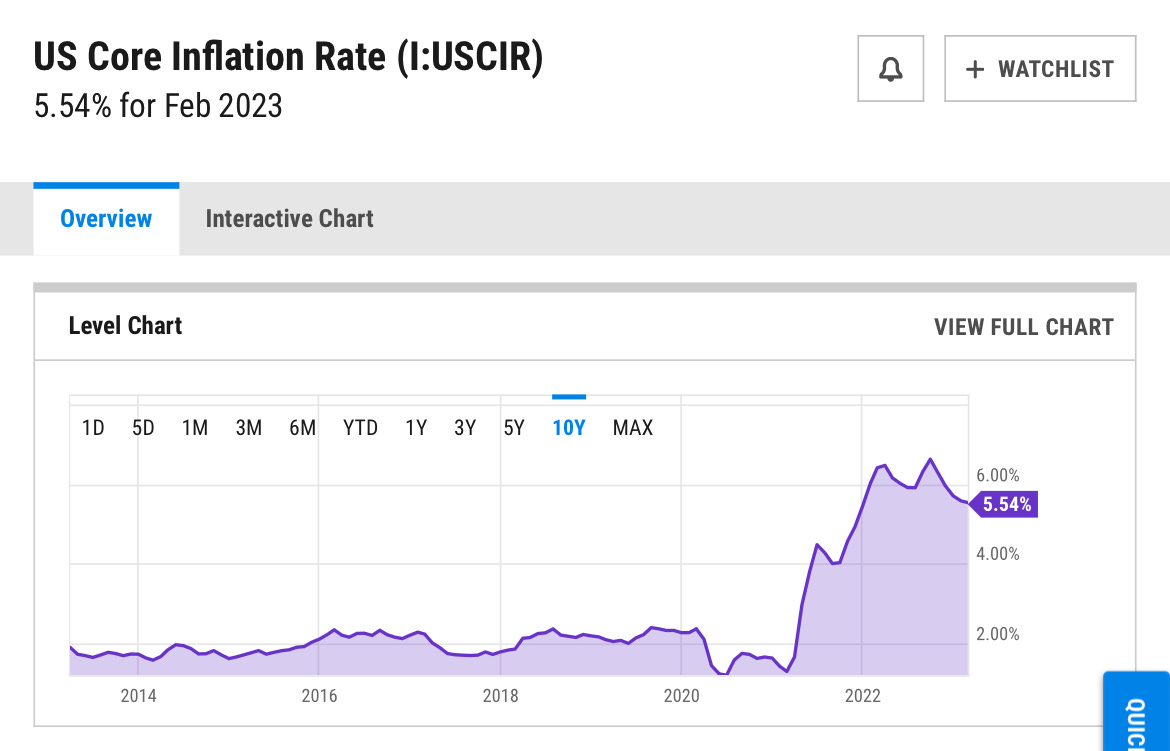

For a long time, all that extra help didn’t seem to matter. Yes, interest rates were artificially low, mightily benefitting to the richest people in the world - on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley. But inflation was also low.

In 2021, though, the bill came due. Inflation suddenly spiked, and it has stayed high since.

To get inflation under control, the Federal Reserve has had no choice but to raise interest rates - and even more importantly, to reduce the size of its balance sheet and thus the amount of money in the banking system.

But the interest rate increases have caused a massive problem for banks. Over the last decade, they grew addicted to paying nothing - as in zero percent interest - on more deposits than they knew what to do with. They parked the money in Treasury notes and other low-risk bonds.

Low credit risk, that is. Those bonds had interest-rate risk like all the others. And when the Fed began to raise interest rates, they lost value. Some banks did a better job managing that risk than others, and - coming back to last week - Silicon Valley Bank did a particularly bad job.

As of last week, the bonds that Silicon Valley held were worth about $16 billion less than it had paid for them.

Coincidentally, Silicon Valley’s entire equity capital base - all the money it had to backstop depositors against all losses - was also about $16 billion. Thus Silicon Valley was effectively broke before the run on its deposits started.

The only question was who would get out whole and who wouldn’t.

—

On Sunday night, the government solved that problem: everyone.

But though extending depositor insurance reduces the pressure for bank runs, it does not magically make banks solvent.

If banks like Silicon Valley have assets (bonds) that are worth less than what they owe depositors, they will eventually fail. And someone will have fill the gap to make those depositors whole.

Other, stronger banks can help, but if the entire industry has lost money because interest rates have risen, the problem will quickly become too big for banks to solve. Then taxpayers will have to step in.

The Federal Reserve (and the White House) desperately want to avoid the appearance of a government bailout - taxpayer money going directly to pay off the wealthiest depositors. The solution is the “Bank Term Funding Program,” a disguised bailout.

These assets will be valued at par - though they aren’t worth par. The Fed will lend money on them, and if banks have to pay back depositors, they can do so with that borrowed money.

The program lasts a year. What then? Everyone will hope that by this time next year interest rates and inflation have fallen and the bonds the banks have pledged to the Fed are actually worth par.

If not, maybe the program will be extended another year, or another 15 years.

—

Worse, what if inflation doesn’t come down? What if it rises, and the Fed has no choice but to keep raising interest rates, and Treasury bond yields also rise? In that case, the bonds the Fed has taken will be worth even less, and the hole on bank balance sheets will be even larger, and bailout will be even larger, and the system will be even more unstable.

Bailouts are very easy to start. And very hard to stop. Especially when sophisticated people have figured out how to make money from them.

What happens next? Where and how does all this end? I don't know. But it WILL end. Eventually these excesses will have to be unwound, gradually or suddenly. When they are, you can bet that all the people who have made fortunes from cheap cash for the last 15 years will be reaching into someone else’s pockets to save themselves - just as they did over the weekend.

And the only pockets left will be the federal government’s.

In other words, yours.

I wonder of the fed would have come riding to the rescue if that bank had been in Ohio and not chocked full of depositors and board members who were major contributors to the democrats

Crazy how the "experts" were "cooling off" the economy when it was only the little people suffering, but as soon as the donor base was threatened, it's PRINT PRINT PRINT. Can't have your buddies going broke!